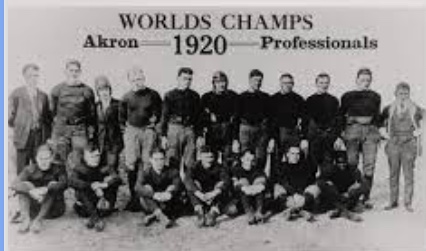

Akron Professionals Championship 1920 Team Photo

NOTE: I am posting a serial about Pro Football Hall of Famer Fritz Pollard, star of the Akron Pros and first Black coach in the NFL. This is Part 10 of 13. Prior posts may be read by visiting my website blog at https://stevelovewriter.com/blog/ or my public Facebook page Stevelovewriter.com

Strangely, the 7-7 tie with Cleveland was one of three during a season in which the Akron Pros finished unbeaten but 8-0-3. Two end-of-season ties, both 0-0, sparked championship controversy, coming as they did at Buffalo and against the Decatur Staleys in a challenge game played in Chicago, where the Staleys soon moved and became the Bears. By creating in 1920 a loose association of teams with too few specifics, the American Professional Football Association (APFA) handed George Halas, who represented Decatur as a founder, the match to ignite a memorable brouhaha.

Akron had survived Buffalo, the All-Americans one of four teams not among the ten represented at the formation of the APFA. They became part of the association by virtue of being a reputable team that played a sufficient number of APFA teams. After proving itself strongest in the East with a 3-1 record against APFA teams, the All-Americans, trying to solidify its championship claim, invited Canton and Akron to play December games, the outcome of which might influence APFA team managers who would pick a champion in the spring of 1921. Buffalo eked out a 7-3 victory over Canton at the Polo Grounds in New York City, the players immediately returning to Buffalo by train to meet the Pros the next day. No doubt fatigued, the All-Americans prevented Fritz Pollard from scoring, and concluded the tie, given the circumstances, was enough to claim at least a share of the championship.

George Halas disputed that claim. Coach of and an end for the Staleys, owned by a Decatur starch company, Halas wanted more than a so-called West championship. The Staleys had played an Illinois schedule, with the exception of Hammond, Indiana. With a 5-1-2 record against APFA opponents and five more victories overall, he proposed to Pollard a December 12 game at Cubs Park. He appealed to their shared Chicago roots. Pollard’s teammates wanted no part of another game, believing they already had won the championship, Buffalo’s claim notwithstanding. They were scheduled to play Canton in an exhibition in Philadelphia but Pros Owner Frank Nied approved the Chicago meeting with the Staleys and Pollard’s teammates acquiesced.

Conflicting memories of Halas and Pollard about the scoreless tie that drew twelve thousand, the largest crowd ever to see a professional game in Chicago, are laughable but led to the lifelong bitterness Pollard felt for Halas. There are certainties, though. Halas added to his roster Chicago Cardinal halfback Paddy Driscoll, who had beaten the Staleys, 7-6, with a drop-kick, as well as another ringer. He did this despite the fact it made a farce of APFA rules he had helped to write. Among the reasons the APFA was formed was to prevent teams from importing non-roster players for key games. Driscoll was the best of such players. What most infuriated Pollard was his belief Halas used him to move the team to Chicago in 1921 when the A.E. Staley Corn Products Company [a.k.a. Staley Starchworks] could no longer afford the team.

Ignore the two touchdowns Pollard told writer Carl Nesfield that he remembered scoring, only to watch them called back for infractions an official later told him had not occurred. Biographer John Carroll found no proof of the touchdowns, much less fraudulent violations. Game reports indicated the field was an ice rink, rendering Pollard and Driscoll ineffective. What galled Pollard was his belief Halas used him to get the game that opened the door to Chicago for him and in subsequent years refused to play first Akron and then Milwaukee, where Pollard played and coached in 1922.

In an interview with Chicago sports columnist Ron Rapoport in 1976, Pollard complained that “George Halas used me to get every goddam thing he could. Then after he used me and got power, he raised the prejudiced barrier. …He was prejudiced as hell.” He told Nesfield much the same. “Halas was the greatest foe of the Black football player. He, along with the Mara family (New York Giants), started the ball rolling that eventually led to the barring of Blacks from professional football in 1933.” [Pollard should have added George Marshall at the top of this list; the owner of the Washington Redskins (Washington Football Team, as it looked for a neutral name), the southern-most team in the NFL in 1933, was among the leaders in slamming the door on Black players.]

Halas denied Pollard’s accusations. “He’s a liar,” Halas said. “At no time did the color of skin matter.” He claimed all that mattered was if a man could play football well, and even admitted that Pollard was “a fine football player … But Jesus!” The last could have been Halas’s reaction to his championship plan fizzling. The league, with Joe Carr in charge after running the Columbus team, awarded the 1920 Akron Pros the first official championship. The Pros received a loving cup donated by the Brunswick Balke Collender Co. as reward but, like so many Pros memories, the cup, forerunner of today’s Lombardi Trophy, vanished long ago.

Akron’s pro football history has been forgotten. (Even Pro Football Hall of Fame historians don’t know what happened to the Brunswick-Balke-Collender Cup, a piece of NFL holy grail.) The team, like those in other smaller NFL cities, was struggling and forced out by financial strife that saw a competitor league born and die in 1926. NFL owners created a new business model that emphasized metro areas. That financial reckoning—it’s always about money—was nothing compared to the NFL’s conflicted racial reckoning that continues, as does Akron’s own.

Akron of the 1920s was run by KKK members. The school board, in particular. Law enforcement. Even the mayor. This probably had little effect on Fritz Pollard, who in 1921 brought his family to live in Cleveland, even though his team practiced in Akron and worked there on Sundays. As the heart and face of the Pros, both star and co-coach, he recruited friend and future activist and actor Paul Robeson, an All-America end/tackle at Rutgers, to join him. Pollard had to have encountered those in the KKK. He shared the attention of the city’s newspapers with the reborn white supremacist organization that bloomed fully in the years Pollard played for other teams and remained a force when he returned to coach and play during 1925 and 1926.

The Klan 2.0, Akron version, resembled the Make America Great Again movement, inspired by Donald Trump during his 2016 presidential campaign, nearly a century later. It believed in America first and only and opposed whatever it deemed less than pure American: foreigners/immigrants, Catholics, and Blacks. When Pollard returned in 1925 Akron’s Klan No. 27, which included Summit County, claimed 52,000 members, most in Ohio and one of the larger chapters—klavens in Klan-speak—in the country. Little wonder Pollard preferred Cleveland, which in 1921, the Associated Negro Press described as a “mecca for colored people.” The Klan, on the other hand, “has always been the champion of white supremacy,” John Lee Maples wrote in a 1974 Master of Arts in History thesis at the University of Akron.

There may have been “no bloodshed or destruction” in Akron during the Klan’s halcyon years but both touched those with whom Pollard could have come into contact. When a reported ten thousand Akron Klansmen headed for a “Konclave” in Niles, Ohio, near Youngstown, some took weapons. They anticipated a battle with the anti-Klan Knights of the Flaming Circle, a rival militant group that admitted those the KKK rejected. When fighting erupted that resulted in injuries, some serious, Ohio Governor A. Victor Donahey ordered in National Guard units, including one from Akron. A number of Klansmen had to leave Niles and return to Akron to join their unit, only to return to the city as peacekeepers. Talk about conflict of interests.

Pollard understood such strife. When in 1923 and 1924 he coached Hammond, Indiana’s lone NFL team, in financial decline and forced to play most of its games on the road, he found himself in another Klan stronghold. He also played for Gilberton in the Coal League. It was the most dangerous of regions—northeast Pennsylvania—for a Black football player, but the money was good, a bidding war driving up the amount a star could earn. Sometimes Pollard even made money on the side, entrepreneur that he was, and in unexpected ways. Gambling was as common during the early pro era as it is today, and those whose teams lost could become violently unhappy.

Pollard was threatened in these inhospitable towns. Police surrounded the field to protect him; fans stoned visiting teams as they went to the railway station. Northwest of Philadelphia in Coaldale, an unhappy loser to Gilberton, thanks in large part to Pollard, a local boxing champion challenged him to fight. Nonplussed, Pollard accepted. He may have been prompted by the same desire that sent him to elementary schools to talk with children. He wanted young and old to know a “modern Negro” and his capabilities.

During the six-round fight the Monday after the game—a major production that must have been profitable, given a full auditorium—Pollard understood his predicament. He was “the only Black man in the whole damn town.” That presented more danger than his challenger, even though the man was larger than Pollard. “This fella,” Pollard told Carl Nesfield, “was just a big bully and didn’t know a lick about fighting.” Pollard did. His father and brothers had taught him well: “I didn’t try to hurt him seriously, because I was afraid of what might happen to me. I just boxed him silly, earning his respect and the respect of everyone in the town.”

NEXT—FRITZ POLLARD BLOG POST PART 11: Pollard Takes a Beating

keep up the good work