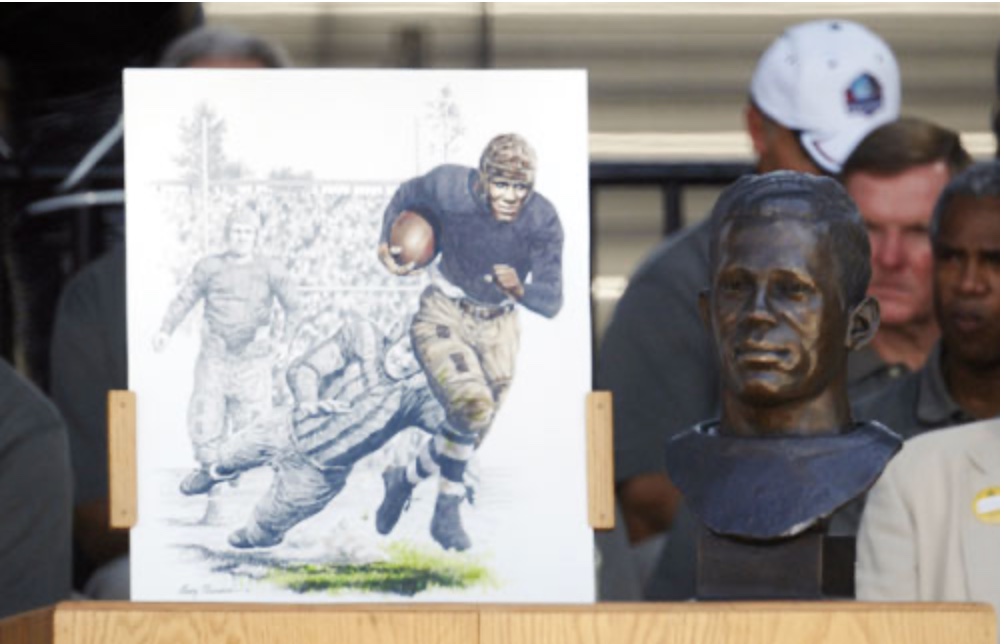

Pro Football Hall of Fame Photo

Fritz Pollard’s mural and bust at his 2005 Professional Football Hall of Fame induction

NOTE: This is the last piece of a 13-part serial about Pro Football Hall of Famer Fritz Pollard, star of the Akron Pros and first Black coach in the NFL. Thanks to those who have read all or part of Pollard’s story. Prior posts may be read by visiting my website blog at https://stevelovewriter.com/blog/ or my public Facebook page Stevelovewriter.com

Even the Professional Football Researchers Association (PFRA), with Fritz Pollard’s life and times—on field and off—readily available thanks to biographer John Carroll, failed to include Pollard in its inventive and compelling Hall of Very Good.

Created in 2002, the Hall of Very Good honors outstanding players and coaches not in the Pro Football Hall of Fame—and perhaps convinces some skeptics of a player’s worthiness of the final highest honor, the Hall of Fame’s Gold Jacket.

I was not a PFRA member in those days—though I should have been, given I had retired from daily journalism and had a deep interest in football history and Akron. Doing research for an Ivy League at Fifty story that was published in February 2004, Brett Hoover discovered to his surprise that Fritz Pollard was not a member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame, and had, in fact, been passed over more than forty times.

Hoover understood that “the story of Pollard is not found in statistics.” Yet stats are the first criterion selectors rely on, and even if they know better, Pollard’s can seem paltry if held up against those from the modern era. Recognizing it was a different time, Hoover compared Pollard to Jackie Robinson, the pioneering Black baseball player thirty years after Pollard arrived in Akron. “Not only was he a great player,” Hoover wrote of Robinson, “he was a great leader, willing to endure personal sacrifices and face extraordinary scrutiny in the face of racism, pain, and adversity.”

He correctly and smartly placed Pollard in the same light—and, intimidating dark shadow—because Pollard “helped to build the league with his legs, his brain, and his reputation.”

The lack of appreciation for Pollard’s role in the NFL’s fledgling years might be attributed to the racial discrimination that dominated the day and led to banning Blacks from the league. Yet when the Akron Beacon Journal asked Pollard about this he acknowledged that while race could have played a role, he suggested he had been overlooked more because of the passage of time. Selectors preferred recent players, the players they knew, Pollard said, Seniors Committee included. In thirty-two years it had only once nominated a player whose career was limited to the 1920s.

Joe Horrigan, former executive director of the Hall, pointed out that Pollard, “marquee player and attraction,” contributed much more broadly than statistics to professional football. Too many took too narrow a view of Pollard. “The Pros were clearly considered major players in the pro game,” Horrigan once told the Beacon Journal, and it was important that they agreed to be a part of the new league. The Pros gave credibility.” And, more than anyone, Fritz Pollard gave the Pros credibility and the first NFL title. He also had, Horrigan added, “the ability to rise above the difficulties he must have faced integrating an all-white sport as a player and a coach. Clearly, he earned the respect of his teammates and management.” If that weren’t enough: “He was also a great promoter and visionary.” Seniors Committee member Don Pierson got it: “I think it was the historical significance of being the first Black player [he was one of the first Black players and the first Black quarterback] and the first Black coach. I look at him as a player, a coach, and a contributor. I think he did all three.” Trifecta! Pollard not only had flash but also substance.

Steven Towns, Pollard’s grandson, argued that his grandfather was “just as important as George Halas and some of the other people [at the dawn of the NFL]. When you read the history, he was right there, a major part of everything that was going on.”

Fritz Pollard did these things when no other Black man would or could, in a city where the Ku Klux Klan ruled the day. “He showed a sense of bravery that’s hard for people today to relate to,” biographer John M. Carroll told the Baltimore Sun when the Hall of Fame announced Pollard as a member of the Hall’s Class of 2005. “He stayed with it and recruited other Blacks into the game.” And when he saw them gradually eliminated as his own career ended, he answered with his all-star teams of Blacks—the Chicago Black Hawks [1927-1929] and the Harlem Brown Bombers [1935-1938].

Long before Colin Kaepernick took a knee during the national anthem to protest racial and social injustice, Fritz Pollard stood tall against it. After the NFL finally bothered to notice what Pollard had done to advance equality in professional football, and the game itself, it apparently again forgot, considering its failed responses to the protests of Kaepernick and his fellow players, mostly Black, seeking redress from the unending prejudice that Fritz Pollard had known so well.

When grandson Steven Towns carried the ball for Pollard at his posthumous Hall of Fame induction he described how scintillating his grandfather had been on the field with comparisons to more recent Hall of Fame running backs. “He had,” Towns explained, “the speed of Tony Dorsett, the elusiveness of Barry Sanders, and the tenacity of Walter Payton.” Today, Towns might well add that his grandfather also had “the courage of Colin Kaepernick.”

Towns lamented while making the induction speech on behalf of Pollard the fact that compared with the lasting presence of Jim Thorpe, his grandfather had become “a footnote” until belated Hall of Fame recognition finally arrived. By then, of course, Fritz Pollard was gone, never knowing that his one last football dream, according to his family, had come true. “Grandpa,” Towns said directly to the late Pollard, “the crowds are cheering.” He pointed out that behind him sat Hall of Famers, who had returned for Pollard’s induction with the Class of 2005, and before him in the audience were others who knew, as Towns put it, that “You’ve more than earned your place in the history of football.”

Before Senator John McCain’s death in 2018 from a malignant brain tumor, he had had the opportunity not only to write, with Mark Salter, The Restless Wave, a final installment of his memoirs but also to watch “John McCain: For Whom the Bell Tolls,” a film that served as living eulogy of McCain’s heroic life of service to his country. As his life from midshipman at the United States Naval Academy to prisoner of war in North Vietnam to United States senator and presidential candidate unfolded, friends, family, and even a few old enemies made clear what McCain had meant to them and to the history of his country. One of directors of the documentary, Peter Kunhardt told the Washington Post: “We wanted John to see this while he still could.” Wouldn’t it have been fitting if the National Football League had given Fritz Pollard this great gift? In an NFL Network segment on the league’s earliest days and African Americans limited place in it, USA Today pro football columnist Jarrett Bell said it all with six words:

“Fritz Pollard is the gold standard”—the gold standard who never had the opportunity to don the Professional Football Hall of Famer’s Gold Jacket that he so richly deserved and to know that his greatness is forever.