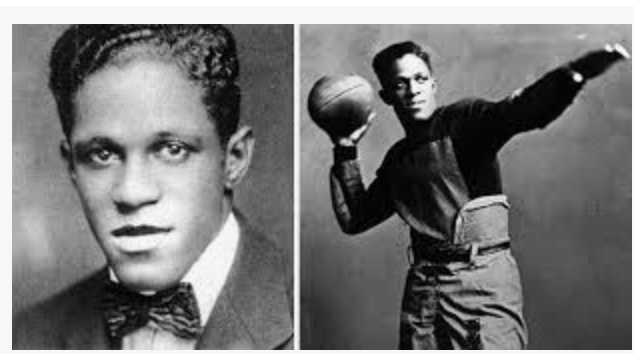

Pro Football Hall of Fame via Brown University Photos

Fritz Pollard grew up in Rogers Park, an all-white Chicago neighborhood before the Pollard family integrated it. Pollard biographer John Carroll speculated that John Pollard, who owned a barber shop, and wife Amanda, who was Black and American Indian, with a lighter complexion, “considered themselves in the upper strata of African-American society.” John Pollard taught his sons to stand up for themselves but avoid unnecessary confrontations with whites, to choose discretion over fisticuffs. They learned both responses well, though Fritz told Jay Berry that neither could prevent the racial discrimination that began “the minute you’re born.”

In backyard football games, Pollard’s older brothers shared survival skills that would come in handy for a Black so small his size could have kept him from playing as a fourteen-year-old freshman in 1908. He and brother Hughes, a junior, were the only African Americans at the new Albert G. Lane Technical High School, and had it not been for Hughes, Fritz might never have gotten his chance to play in 1909.

Hughes, whose athletic career was short-lived because he preferred music, confronted Lane Tech’s principal and coaches when it looked as if his eighty-nine-pound brother would not be allowed to play. He told them: No Fritz. No Hughes. Fritz played and became a Chicago schoolboy whiz at a time another small player at Crane Tech, 110-pound George Halas, could not make the varsity and so did not come head to head with Pollard. In later years their paths would cross often or, as Pollard would say, collide.

As intelligent as Pollard proved he was throughout his long life, there is, frankly, no explanation for why, after high school, he tramped from college to college, team to team. He pleaded naïveté.

How could that have been? Brother Leslie had played football at Dartmouth University. Sister Willie Naomi Pollard was a brilliant student at Northwestern, the first Black woman to graduate from that university. They offered examples and direction. His sisters, including Ruth, who died young and could outrun Fritz, demanded that he study. Something went wrong.

As much as I admire Pollard and feel a kinship with him, his behavior baffles. If he was naïve, he was immature as well. How could he not know the drill for choosing a college—and team—receptive to Blacks and present himself well prepared? Even if college admission differed from today—especially for athletes—it would have been ill advised to show up at Northwestern and announce to the dean of admissions that first and foremost he was there to play football. He had begun practice with the freshman team but had not yet applied for admission. Education? Classes? Not Pollard’s priority. His proud sister’s university sent him packing.

Before he found a less-than-welcoming home at Brown, Pollard received an education in hard knocks and racism, first as a small, young hotshot with an Evanston semipro team in 1912. When the team went on the road, those who had not admired Pollard the high school star reminded him he was nothing but a “Nigger” to them. That word rained down on him, and there was no outrunning or eluding it. It would follow him to the Ivy League, across America to the Rose Bowl, to Akron and beyond in the pros, including in Pennsylvania’s brutal Coal League.

Pollard had no map that took him to Brown. His mother continually laid out the small Baptist school’s advantages she had learned from Elmer T. Simmons, an owner of Chas. A Stevens & Co., a Chicago department store for which she had done seamstress work. She shared with her son Brown’s football history. Fritz seemed more interested in following in brother Leslie’s footsteps at Dartmouth but on his way to Hanover, New Hampshire, in January 1913, he stopped in Providence, Rhode Island, and became captivated by the gleaming edifice atop College Hill.

Pollard used the experience of his Northwestern faux pas and visited the dean of admissions, where his education in the difficulty of launching an education continued. Brown did not admit midyear students, but Dean Otis Randall allowed Pollard, so far from home, to remain as a special student. Because he had attended a technical school, he lacked the foreign language credits necessary to become a regular student. His family scraped together money to send him to Columbia in New York City during the summer to study French and Spanish.

When Brown accepted what amounted to the equivalent of two years of French but refused to do the same for one year of Spanish, it must have reminded Pollard of how he felt being turned away by Northwestern. He hid from his family that he was not attending Brown, mooched meals from friends, found work, and fell in love with the daughter of his landlord.

His football dream derailed, he eloped with his pregnant girlfriend, and they married against her father’s wishes. Pollard’s biographer judged Fritz’s behavior more than “irresponsibility” and “immaturity.” He thought it “rebellion against the discipline and high level of accomplishment his family demanded.” Pollard could be thoughtless. He told no one except brother Leslie about the mess he had created for himself and his wife, Ada. Leslie suggested he try Dartmouth. Any port/school/team in a storm; the seas of Pollard’s life were roiling.

For the blink of an eye, Hanover, New Hampshire, looked as if it might offer the safe harbor that Fritz Pollard had been floundering to find. Leslie Pollard may have laid groundwork with Dartmouth coach Frank W. Cavanaugh. Cavanaugh seemed to know Fritz was going to show up before he did, in September 1914.

He picked up his football gear, registered for classes, found a place to stay, and discovered some of his new teammates had been opponents in Chicago. Cavanaugh, a big, tough World War I hero, set expectations—winning—and Pollard dreamed of leading the way. Though to Cavanaugh neither race nor size was an issue, he warned Pollard that others would not be as accommodating toward a Black man. Could Pollard handle the discrimination he would encounter. “I always have so far,” Pollard said. He would swallow hard, play harder, and prove his worth.

The Dartmouth dean called Pollard and demanded to know if Pollard had attended Brown. Pollard explained he had been a special student. He had not mentioned this when registering for classes. Dartmouth frowned upon student-athletes who jumped from college to college. The dean told Pollard he would have to leave. Had Pollard again proved his naïveté or had he intentionally omitted what he knew could be a disqualifying stop on his vagabond athletic journey?

NEXT—FRITZ POLLARD, BLOG POST PART 4: A Black Back at Brown