When a man of a certain age and stage turns his thoughts to questions of promise, it is those of the past rather the future that march most loudly through the mind. Considering how the Cleveland Browns and other NFL teams are spending their free-agent money to enhance their rosters as the league’s new year begins brings this contrast forward.

As I wrote in my last post about this forward-looking promise, my mind kept drifting to a favorite book—football or otherwise—that I have been rereading, probably for the last time. The author, Jay Cronley, is a favorite, too, for reasons as complex as the author himself was. I still cannot get used to placing Jay in a sentence that is past tense.

Jay Cronley died four years ago in February, but I did not know this until the Tulsa World, the newspaper on which I grew up to compete with as a sports columnist at the Tulsa Tribune, did a year-end retrospective of Tulsa’s important losses in 2017. For me, there was none more important than Jay. In the mid-’70s, when he wrote, Fall Guy, his first of a number of humorous novels, we were colleagues at the Tribune. On good days, we were friends. But to step out onto that unstable ledge with a resolute description of our relationship as a friendship would probably cause Jay to haunt me.

I knew my place, and he knew his. Jay was Top Dog. I was simpering puppy. He was mentor. I was mentee. But even that is too clean a description of our relationship. He had an office because he was a Tribunecolumnist. I had a desk—and felt lucky to have that—in the proximity of his office door where only the brave dared to enter. I was brave—and stupid. I would risk the famous Cronley wrath, which was something to see but less fun if you happened to be its target. Mostly, I was not. Jay liked talking writing, and I appreciated the opportunity to listen to him do so. We even did this in off hours.

For a time, Jay and his wife, Connie, lived in a downtown Tulsa highrise apartment building of some stature. Don’t know how my wife Jackie, also a journalist, and I got in. We had a lower-rent one bedroom on the 18th floor, and the Cronleys a larger two-bedroom on a higher level, in every sort of way. It was there that Jay invited me to meet one of his writer friends, Evan Hunter, an established star in the pantheon of letters. Fall Guy is dedicated to Evan, along with Jay’s “ladies”—Connie and daughter Cinnamon.

I do not know this for a fact, and with Jay’s remarkable talent it would be wrong to assume how much Hunter aided Jay’s start as a writer of fiction, but, as one who never had this kind of friend nor Jay’s talent, I can only image that Hunter’s advice helped. Actually, as much as is possible at a newspaper, Jay took the facts of the day and when they popped out of his column they had become golden baubles, magically transformed.

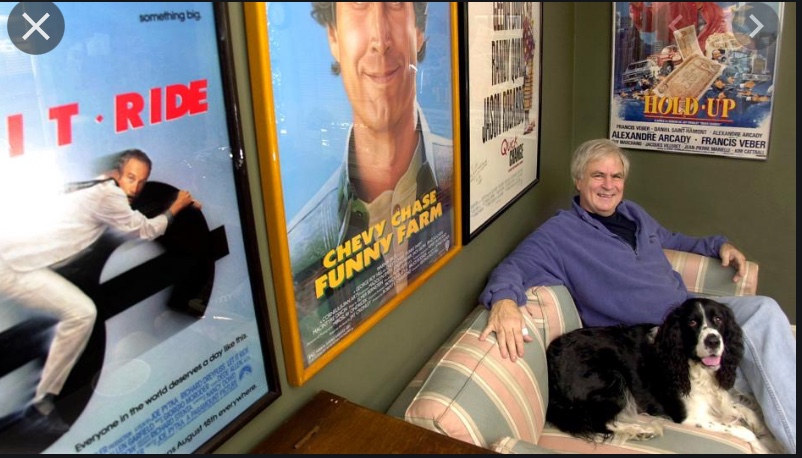

Jay Cronley did the same in Fall Guy, as in his novels which became more famous and movies, if not always better than the original ink-on-paper. That list includes Good Vibes (Let It Ride), two versions of Quick Change, and Funny Farm. If Fall Guy had fallen at the end of Jay’s 20-year books-to-movie bonanza, I think that it, too, would have become a film. It is Semi-Tough (Dan Jenkins), amateur version. I can testify how right Jay got the difficulty of some high school football stars’ transitions to college football. Jay, son of distinguished and highly decorated Oklahoman sports editor John Cronley—father and son are in the Oklahoma Journalism Hall of Fame—was himself, in fact, an All-Conference second basemen at the University of Oklahoma. He also wasn’t a bad hand shuffleboard player. He cleaned my clock like clockwork at Arnie’s, the bar hangout of choice for Tribune newsies and Cronley sycophants.

Jay created a believable high school running back, Ben Elliott, who was the hottest commodity above ground in Texas. A state champion, Elliott might as well have been a piece of taffy, so stressed to the max was he during the recruiting tug-of-war between Texas and Oklahoma schools. An unidentified Texas school won but not because both schools could not have given lessons on how to cheat in recruiting and get away with it. During a lengthy journalism career, much of it spent covering both high schools and colleges, I recognized both sides of that tarnished coin. To make fiction even more realistic, Ben had a widowed father who loved his son and lived through his exploits.

A person could laugh until they hurt as much as Ben did when he got to college and discovered that catching and fair catching punts can be dangerous to a person’s health and promise. Laughs were a serious part of Jay’s life, on the page and at home. Connie Cronley, a wonderful writer in her own right, makes that point right away in her book Poke a Stick at It: Unexpected True Stories. She introduces her first essay, “My Ex-Husband” (don’t ask how that happened) by acknowledging, “Nobody makes me laugh like my ex-husband. Nobody is more exasperating, tells bigger whoppers, or keeps life real like my ex-husband.” Her description could fit more than one character in Fall Guy.

Jay even makes death almost laughable. And he does so with language that I, denizen of locker rooms and newsrooms, found not only comfortable but also necessary for believability, even if it is likely to offend Puritan readers. One of Ben Elliott’s notorious teammates, linebacker “Prison” Cornelius believes almost everyone, especially coaches, is a mother-F-er. in my experience Prison’s only rival in the use of this term is either brilliant former Mayor Don Plusquellic of Akron, Ohio—or not-so-brilliant me.

If this is a funny story, it is not always a happy one. Ben Elliott’s great promise is squandered—what coach puts his future Heisman Trophy candidate at risk as a punt returner?—and he and his daddy end up back home in the small west Texas town of Arnold, trying to piece together in their crazy minds what the hell happened.

Even the closing scene is darkly funny and typical of a bad day in Tornado Alley—Texas, in this case, but even more so Oklahoma. People and pieces of places can be here one second and gone in another. It is all a part of the great mystery of great promise and Jay Cronley got it. He put into Ben Elliott’s mouth a closing line that would have made the great Hemingway envious, given the number of times he rewrote (39, or more) the ending of his World War II masterpiece, A Farewell to Arms.

With a singular, common gesture, the painting over of a sign at the outskirts of Elliott’s hometown, Cronley makes us understand that promise, neither future nor memory of it, is assured.

Great article Steve, really enjoyed it.

good article. I knew Connie well. I only knew Jay through reading. I followed each of them and agree that Jay was a good writer and Connie remains a good writer. thanks to another good writer.

Two writers from little Nowata, Oklahoma? Who would have “thunk” it. I will always be grateful for the great teachers I had growing up in Nowata. They laid the foundation. Others in California added to it and

opened additional doors. Education can be magical.

Thanks for thinking aloud about my father. I love that you understood him. He was complicated. And brilliant. And hilarious.

Thanks for this article, Steve. Good job. It brought those Tribune and Center Plaza days sharply to mind and inspires me to reread Fall Guy.

Thanks to you, Connie and Cinnamon. I appreciate both the time you took to read the post and to make a note of it here. Only wish that Jay were still here physically for you and rest of us. I am grateful, though, for his books and memories of him.