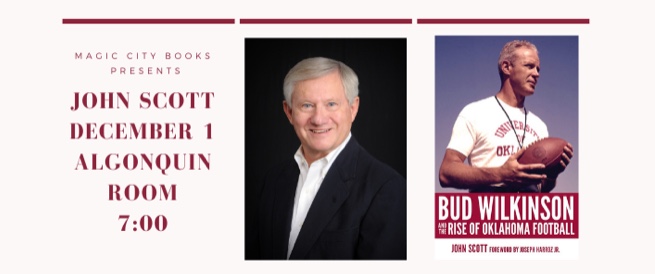

John Scott is anything but a slow study yet it took him years to complete his marvelous archetype of learned sports biography. He began Bud Wilkinson and the Rise of Oklahoma Football in 1986. It wasn’t published until 2021. Do the math. It took Michelangelo less time (1508-1512) to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

Neither was a small project. Both are works of art and tell valuable stories. Michelangelo’s celebrated work has stood the test of time. Scott’s was worth the wait not only for followers of Oklahoma football but also of the broader college game.

So as not to punt the art metaphor, if someone should sculpt a football-coaching equivalent to Mount Rushmore National Monument, Wilkinson would be a rock-solid choice. He was one of the game’s seminal minds during 17 seasons (1947-1963) that imprinted OU football on the landscape as a monumental program, as he provided model leadership. His teams won three national titles and peeled off a still-record win streak of 47 games, after a previous run of 31. Yet Wilkinson’s greatest legacy may have been his comportment and what players learned from it, particularly those such as Darrell Royal whom Wilkinson helped to land the Texas head coaching job, even though the Longhorns are Oklahoma’s bitter rival and teacher could not afford losses to pupil.

Scott, as he explains in his preface, began researching and writing what was intended to be a “distinctive coffee table book” with illustrations by Tulsa artist Jay O’Meilia. He interviewed Wilkinson for “five full days” in the summer of ’86 and by 1987 had produced a manuscript to review. By early 1988 Wilkinson not only had read and approved the first draft but also wrote to Scott to tell him: “Your explanations of football strategies are concise and clear. They rank among the best I have ever read.”

This was high praise from a master strategist of the game to a writer who is as good—not to mention fussily precise—as any I have known. John Scott and I grew up on Wilkinson and OU in Bartlesville and Nowata, small and smaller Northeast Oklahoma towns 20 miles apart. Years later, we became colleagues and friends at the Tulsa Tribune. It did not surprise me to learn that Scott had “worked through more than a dozen revisions of the manuscript, all of them oriented toward focusing the narrative more narrowly on Wilkinson himself.” He succeeded without sacrificing the mini-profiles of famous coaches who were “friends and among the most successful coaches of the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, including Royal, Bear Bryant (Kentucky, Texas A&M, and Alabama), Frank Leahy (Notre Dame), Earl Blaik (Army), and Jim Tatum, with whom Wilkinson came to Oklahoma before succeeding Tatum (Maryland and North Carolina).

Scott weaves his tangential characters into a narrative that neither lags nor wavers through chapters of seasons that educate those who did not know Wilkinson and his teams and re-educates those of us who lived with and through them, first as childhood fans and later as writers. In fact, I use some of the same sources and material as Scott—neither as extensively nor as well—in Football, Fast Friends, and Small Towns: A Memoir Straight from a Broken Oklahoma Heart (2020).

Whereas my book is more personal, Scott has weeded out the extraneous and tightened the focus on his historic figure, on and off of the field. The Wilkinson that shines brightly from Scott’s pages is a complex man (and character) whose interests exceed those of coaches who might not have recognized football strategy in military history, including Infantry Attacks, by Field Marshall Erwin Rommel, the German tank commander, The Art of War, by Chinese general Sun Tzu, and, to understand governing and playing politics, political theorist Niccolo Machiavelli’s The Prince.

Wilkinson learned his lessons well. He was a Renaissance Man in T-shirt, with whistle around his neck. He extrapolated military maneuvers to the Split T option play that he learned from Don Faurot, Missouri coach before World War II Naval service. Wilkinson added his own twist that turned it into a Triple Option, with which Barry Switzer’s wishbone offense added national championships in Norman. Machiavelli’s governing advice he applied to university politics and, in the end, to a desire to broaden his horizon to political office. So effective was Wilkinson that before Switzer and Bob Stoops built on his foundation, George Cross, university president, famously told the Oklahoma legislature, with whom he was squabbling about funding, that he needed money “to build a university of which the football team could be proud.”

If Bud had listened to his father, C.P. Wilkinson, a mortgage banker, he might never have become such an influential coach that he made more money than Cross. The senior Wilkinson warned his son that “No matter how able or successful he may be, every coach eventually reaches a point where a lot of people want somebody else.” Though eventually his son bumped up against pushback, usually it involved others wanting to lure him away from Oklahoma. He listened but never took the bait.

Even when he no longer had the older, mature WWII veterans who came home to Oklahoma to help Wilkinson build a dynasty in the late 1940s and into the 1950s, Wilkinson and a fellow former Big Ten star, line coach Gomer Jones, found answers to the challenges they faced when Oklahoma’s small-town talent dried up. He did this with thoroughness and quickness of mind that made him a true and great leader-teacher.

Wilkinson’s students were some of the toughest, most talented that Oklahoma small towns ever produced, from the Burris boys from Muskogee to years later on Switzer’s championship teams, the Selmons from Eufaula. There were players of great character as well as characters who played great—from the little New Mexican Tommy McDonald, who ended up in the Pro Football Hall of Fame and never changed from the days he was a riotous OU talent, to Joe Don Looney who lived up to his name. Scott brings them all back to life—most sadly gone now—as seamlessly as a dream-weaver.

Even after a falloff of talent and results—Wilkinson finished with a 145-29-4 record—he and Jones resurrected the Sooners. Yet with the death of longtime U.S. Senator Robert S. Kerr on New Year’s Day of 1963, Wilkinson recognized an opportunity to move beyond football. A registered Democrat—Oklahoma was a state of “yellow-dog Democrats” who would rather vote for a yellow dog than a Republican—Wilkinson had led John F. Kennedy’s Council on Physical Fitness. But he began to explore running for Kerr’s U.S. Senate seat as a Republican, given that state senator Henry Bellmon had wrested the governor’s office away from the Democrats in 1962. It was a grave miscalculation, as he found himself tied to Barry Goldwater’s flaming coattails in Lyndon B. Johnson’s landslide presidential victory of 1964.

The brilliant strategist who could assess any situation on the football field and find a path to victory, failed himself. Was he blinded by desire to be more than the football coach on which his father had frowned? He resigned as coach at the end of the 1963 season but would have remained athletic director for a time had university trustees not pressured him to step aside if he wanted his faithful lieutenant Jones to have his job.

Scott, as he did throughout the telling of Wilkinson’s story, recognized the coach’s prescience. “Wilkinson knew Jones was not emotionally equipped to be a head coach. And he knew that Jones also knew it,” Scott wrote. “But with the kingdom the two of them had created there for the taking, Jones could not sit idly by and abdicate it to another who had not earned that right, and though he could foresee a tragic ending, he could do nothing to forestall it. . . . Wilkinson concluded Gomer deserved his chance.”

Wilkinson got out of the way. He announced he would also resign as athletic director and “recommended that Jones be named football coach without delay. Wilkinson knew it was the only thing—the only right thing—he could do.”

Neither football nor politics is bean bags. Jones had a 9-11-1 record in two years but resigned and remained athletic director, the failure Wilkinson feared. Wilkinson suffered his own failure. The yellow dog won the senate seat. There was nonetheless stardust to sprinkle on Wilkinson’s fairy-tale life had Scott’s story had already concluded. This was Wilkinson and Oklahoma football’s rise. That story had ended before Wilkinson, too, suffered two humbling seasons (9-20) coaching the NFL’s St. Louis Cardinals.

He had, however, already proved that he could be as good, concise, and clear as a college football commentator as he had judged Scott’s writing. Unlike Scott, though, he did not have the benefit of time on television—or was it a plague?—to revise and revise again his words. First the 1986 oil-price bust prompted Tribune Swab/Fox to decide “the market for a luxuriously illustrated coffee table book no longer existed.” It was not until 1997 that Scott was able to purchase the rights to his manuscript that TSF held.

It was in hindsight, I think, a fortuitous turn of events. As captivating as Jay O’Meilia’s football art is—I still have a treasured piece—this is a book served best by an instinctual Oklahoman’s narrative and the precisely woven scenes that he was born to write.