Author’s photo

Though the situations differ drastically, it can be instructive—if terrifying—to recall the first college football program to attempt to climb the rungs from one NCAA division to another, from one conference to another, with a sojourn as an independent.

It happened in Akron 35 years ago.

The lesson remains fresher than ever because of the wholesale conference realignment that began this fall with Oklahoma and Texas announcing that they will be abandoning the Big 12 Conference and hooking up with the spiffier, richer Southeastern Conference, date to be determined but sooner than later. If USA TODAY sports columnist Dan Wolken is correct—and he usually is—so many additional shoes will drop between now and the end of the calendar year that it could further shake already shaky ground. The football foot soldiers on the march could cause the earth to move.

Money and prestige began this latest round of realignment. To replace the Sooners and Longhorns, the Big 12 has turned to four teams with whom it has exchanged vows—Cincinnati, Brigham Young, Houston, and Central Florida, all but BYU current members of the American Athletic Conference (AAC). That wasn’t the way it was in 1985.

No one offered the University of Akron a safe-and-sure landing spot when William Muse, then president, told newly hired athletics director Dave Adams that he wanted to move the Zips out of the Ohio Conference and what was then Division I-AA—equivalent of today’s Football Championship Subdivision—and into I-A, now Football Bowl Subdivision. Muse thought top-rung football would further elevate a growing school.

Akron has achieved whatever status it has more on its Polymer Science and Polymer Engineer programs and sports such as soccer and, to a lesser degree, basketball. But Muse had a plan, and Adams had a coach in mind—Gerry Faust—whom he believed could attract the attention that would be needed to launch an independent I-A program.

Faust had a job at a great university with one of the higher-profile and most historic football programs in America. Everyone in college athletics and in the sphere of influence at Notre Dame knew that Faust was not long for the job he had won straight out of Cincinnati Moeller High School because his Catholic high school team had achieved such fabulous success that its profile was higher than that of many college teams. Faust was the perfect fit for Notre Dame—devout Catholic, great guy who treated people right and whom his players loved—except for one thing. He did not win enough games, which at Notre Dame would have amounted to all of them. He was in his fifth season with a 25-20-1 record and on his way to his second and final 5-6 record.

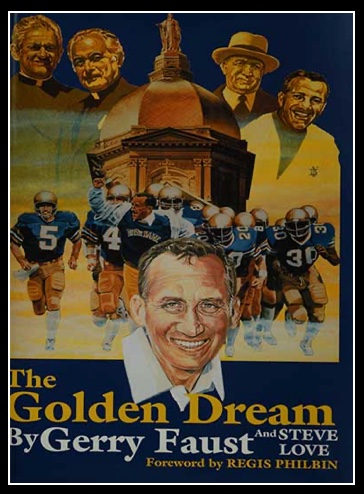

Adams recognized that Faust soon would need a job. The only thing was, Faust didn’t want Akron’s. Despite his 30-26-1 record—he had been 174-17-2 at Moeller—he still saw himself as a Division I-A head coach. “I didn’t want to go to a I-AA school,” Faust said in the1997 book The Golden Dream. “I wasn’t even sure I wanted to go to one that had ambitions of becoming the first school ever to move up to I-A. Right or wrong, it just didn’t appeal to me. What I was really interested in were the I-A offers, especially Rice, which wanted me in two capacities, coach and athletic director.” But, Ohio was home.

No coach wins at Rice, the academically demanding school then in the Southwest Conference. It is a university that means it when it refers to football players as student-athletes, emphasis on student. But if Rice would have been difficult, continuing Akron’s I-AA success at the I-A level proved to be all but impossible, even after it scaled back its ambitions—Faust was opposed—to the lower I-A Mid-American Conference.

Faust did succeed. His dream of improved athletic facilities led to a field house and eventually a stadium, but his Akron teams were up and down despite his ability as a recruiter and he no longer was coach. He had two seven-win seasons and one of six in nine years. After a 1-10 record in 1994, the university gave him an administrative job.

Realignment, whether division or conference, does not always work as planned. Rice, for instance, has been sliding in conference status, from the Southwest to Western Athletic to Conference USA. The only smaller FBS university is Tulsa of the AAC, which is likely to add three or more schools to replace the three it lost to the Big 12.

In addition to membership changes forced upon some conferences, the NCAA soon will hold a constitutional convention to reconsider a structure grown more unwieldy as it has increased in size, the schools at the top having little in common athletically with the schools toward the bottom. The latter includes Akron, 35 years and many coaches later.

Conferences are forced to raid and scavenge or get off the merry-go-round. “One thing everybody agrees with is that Division I is too big,” one athletics director told Wolken who spoke with 17 people about realignment. “At some point, there has to be a line.”

Small colleges which play in the NCAA’s Division III do not offer athletic scholarships but use sports as a recruitment tool and provide athletes, as well as students who do not participate in sports, financial aid on a need basis. When I worked as Director of College Relations at Hiram and supervised sports information, I came to appreciate how much athletics not only enhance the college experience for those who participate but also for the campus as a whole, students and those who teach them. Good high school athletes who want to continue to compete but are not recruited by FBS or FBC schools often consider colleges where they believe they can play. That boosts enrollment.

Known as an excellent recruiter, both at Notre Dame and Akron, Gerry Faust had to have a sharper eye for talent that others overlooked when he was at Akron and trying to find athletes who could aid Akron’s transition from Division I-AA to I-A. One of those whom he found was Jason Taylor, a defensive end who went on to a career mostly with the Miami Dolphins that earned him a bronze bust in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

There just weren’t enough Jason Taylors to make Akron a winner. Still aren’t.